- Feb. 27, 2024

- Siddhi Talgaonkar

- Microbiome and Disease

How Your Microbiome Influences Cravings and Eating Disorders

Craving for a pizza, burger, fries, cold drinks, panipuri, samosa, or vadapav (add your favorite snack of all time)? Have you ever felt like eating too much food without knowing how much you ate? Or have you ever felt like eating nothing because you might gain weight?

So, this emotional eating, or eating according to your thoughts, is normal for all of us. But what if we told you that this emotional eating could be an eating disorder?

Eating disorders are severe psychiatric conditions, primarily encompassing mood and anxiety disorders along with obsessive-compulsive disorders, characterized by extreme weight fluctuations and disruptions in hunger regulation. These illnesses, which can be grave and even fatal, manifest through significant disruptions in eating patterns alongside corresponding thoughts and emotions. It affects up to 5% of the population and typically begins in adolescence or young adulthood. These can be extremely dangerous conditions that interfere with social, psychological, and physical functioning.

What are the causes?

While precise causes remain elusive, experts posit that a blend of factors, including genetics, social dynamics, physical health, and psychological factors, contribute to the development of eating disorders. Psychological factors such as being more susceptible to depression and anxiety, having trouble dealing with stress, worrying excessively about the future, having perfectionistic tendencies, having trouble controlling one's emotions, feeling obsessive or compulsive, and being afraid of being called "fat" or overweight lead to interrupted eating habits. Genome-wide association scientific studies (which help to identify genes related to disease) have discovered distinct genetic polymorphisms linked to eating disorder risk, emphasizing the intricate interaction of genetics and environment in their development.

However, the gut microbiome research on this topic has caught the attention of the researchers as it is related to neuropsychiatric disorders, metabolic disorders, and immune-mediated diseases, which indirectly are related to the factors affecting eating disorders.

The alterations in gastrointestinal functioning disrupt the circadian rhythms (the body's internal clock) by influencing the timing and release of hormones involved in digestion, such as leptin and ghrelin, which control hunger and the metabolism of energy.

The synchronization of peripheral clocks in the stomach with the gut circadian clock can be disrupted by irregular eating patterns. This can result in disruptions to general metabolic processes, nutrition absorption, and digestion.

Excessive dietary restriction prolongs the time that food remains in the stomach by slowing down the process of gastric emptying. Prolonged transit times might cause constipation by interfering with regular bowel motions. It also modifies the makeup of the gut flora, giving preference to microorganisms linked to diet restrictions. These modifications to the gut flora may help to develop or exacerbate restrictive eating behaviors by extending the cycle of food restriction.

Gut microorganisms may have an impact on hunger and satiety hormones such as leptin, ghrelin, peptide YY (PYY), and neuropeptide Y (NPY), which are implicated in eating disorders. Under normal physiological circumstances, leptin suppresses appetite, while ghrelin suppresses hunger. Different conditions cause various types of eating disorders, specifying different gut conditions.

Types of Eating Disorders

Img-1: Potential signs of an Eating disorder.

A few indicators of eating disorders are shown in the image above, including worrying excessively about one's weight and visual appeal, exercising excessively because one is preoccupied with being overweight and maintaining abnormally high electrolyte levels. Consuming unusually large amounts of food without tracking how much is consumed. Experiencing occasional anxiety and food avoidance.

International disease classification systems recognize seven distinct eating disorders. However, the three most prevalent among humans globally are Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN), and Binge Eating Disorder (BED), while others include rumination disorder, pica, avoidant food intake disorder, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID).

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is a severe eating disorder characterized by severe dietary restriction, which leads to dangerously low body weight and a deep-seated fear of gaining weight. A psychological profile characterized by a strong desire to be skinny and unhappiness with one's physical appearance is typically the core cause of this condition. Furthermore, about 40% of individuals with AN experience a substantial drop in their bone mineral density (BMD), which increases their lifelong fracture risk by three times. According to epidemiological statistics and genome-wide association studies, people with anxiety and depressive illnesses may be susceptible to AN. Symptoms of extreme dehydration include dizziness or fainting, as well as brittle hair and nails, cold sensitivity, and muscular weakness. Vomiting may cause heartburn and reflux, and severe constipation and bloating which are frequently followed by a feeling of fullness after meals are typical gastrointestinal symptoms. Obsessive exercisers run the risk of stress fractures and bone loss, which can develop into osteopenia or osteoporosis. The psychological effects of eating disorders might also include exhaustion, melancholy, irritability, anxiety, and poor focus.

Bulimia Nervosa (BN) is characterized by the disappearance of enormous amounts of food, persistent sore throats, and enlarged salivary glands. The term "binge eating" refers to eating a lot of food quickly and feeling out of control of what or how much is consumed. Binge behavior is frequently hidden and accompanied by emotions of guilt or humiliation. Food is frequently ingested quickly, beyond fullness, to the point of nausea and pain, and binges can be quite enormous. At least once a week, binges happen, and in order to avoid gaining weight, "compensatory behaviors" are usually engaged thereafter. Fasting, vomiting, laxative abuse, and obsessive exercise are examples of such behaviors. People who suffer from bulimia nervosa may be underweight, average-weight, overweight, or even obese. Heartburn, laxative or diuretic misconduct, and dental deterioration due to erosion caused by stomach acid are other prevalent symptoms. Frequent, unexplained diarrhea and dehydration from excessive purging behaviors may be signs of borderline personality disorder (BN).

Binge Eating Disorder (BED): Like bulimia nervosa, patients suffer phases of binge eating during which they eat a lot of food in a short amount of time, feel as though they have lost control over their eating, and are upset by their excessive behavior. They do not, however, frequently engage in compensatory behaviors to get rid of the food, such as forced vomiting, fasting, exercising, or abusing laxatives, unlike those who suffer from bulimia nervosa. Serious health issues, including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disorders, can be brought on by binge eating disorders. The diagnosis of binge eating disorder involves frequent binges (at least once a week for three months), along with three or more of the following features:

- Eating until their stomachs hurt.

- Consuming a lot of food even when not hungry.

- Eating alone due to embarrassment about one's appetite.

- Feeling extremely guilty, unhappy, or dissatisfied with oneself following a binge.

Here are a few other eating disorders, explained briefly -

A recently characterized eating disorder called Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) is characterized by high pickiness and a chronic inability to achieve nutritional demands due to an eating disturbance.

An individual with Pica, an eating problem, would often consume non-food items that are devoid of nutrients. Depending on the age and accessibility, common materials consumed might be anything from paper to paint chips, soap, fabric, hair, string, chalk, metal, stones, charcoal, or clay.

Rumination Disorder is characterized by recurrent episodes of food regurgitation and rechewing after eating, in which the food is willingly pulled back up into the mouth, chewed again, swallowed again, or spit out. Rumination disorder can strike throughout early life, childhood, adolescence, or even as an adult.

How are these eating disorders related to the gut?

Every person's gut microbiota is different and is impacted by a variety of factors, including geography, age, sex, food, health, and drug exposure. An imbalance in microbial species, known as microbial dysbiosis, is frequently associated with several diseases. The gut microbiota plays an important role in drug detoxification, immune system training, and vitamin synthesis. It also affects host behavior modification, diet-induced energy extraction, and weight management via direct and indirect pathways. Overall, it is an essential component in preserving many aspects of health and well-being.

Dysregulated calorie and nutrition intake may impact gut bacteria metabolism in eating disorder individuals. Research on animals indicates a link between the gut microbiota and characteristics of eating disorders, such as dysregulated behavior and energy balance.

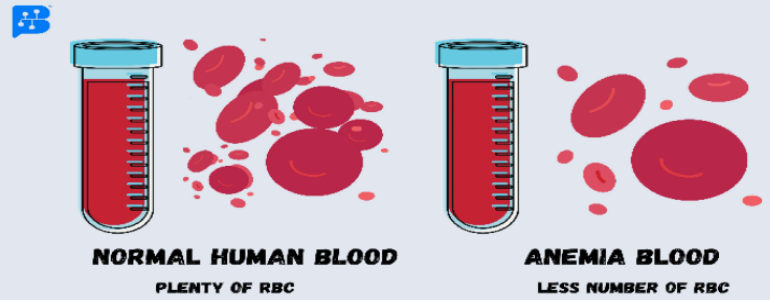

α-diversity refers to the diversity of bacteria in an individual ecological community. Research has shown that higher α-diversity correlates with better health. A reduction in gut microbiota diversity, particularly among butyrate-producing bacterial species, is linked to increased anxiety, depression, and eating disorder (ED) psychopathology. This shows that the gut microbiota may be the missing link in our knowledge of eating disorders (EDs) by having a significant impact on eating behavior and mental health. Research findings reveal a negative correlation between α-diversity and ED psychopathology, encompassing depression and body image issues. Poor nutrition in anorexia nervosa (AN) can alter the internal structure of the small intestine, decreasing its capacity to absorb nutrients and making weight gain more difficult. Purging behaviors, such as vomiting, can damage the stomach lining and alter its function, resulting in stomach disorders. Misusing laxatives in AN or bulimia nervosa (BN) can result in chronic diarrhea, electrolyte abnormalities, and bowel movement problems. In AN and BN populations, a lower BMI is linked to a greater prevalence of E. coli in the gut.

Treatments

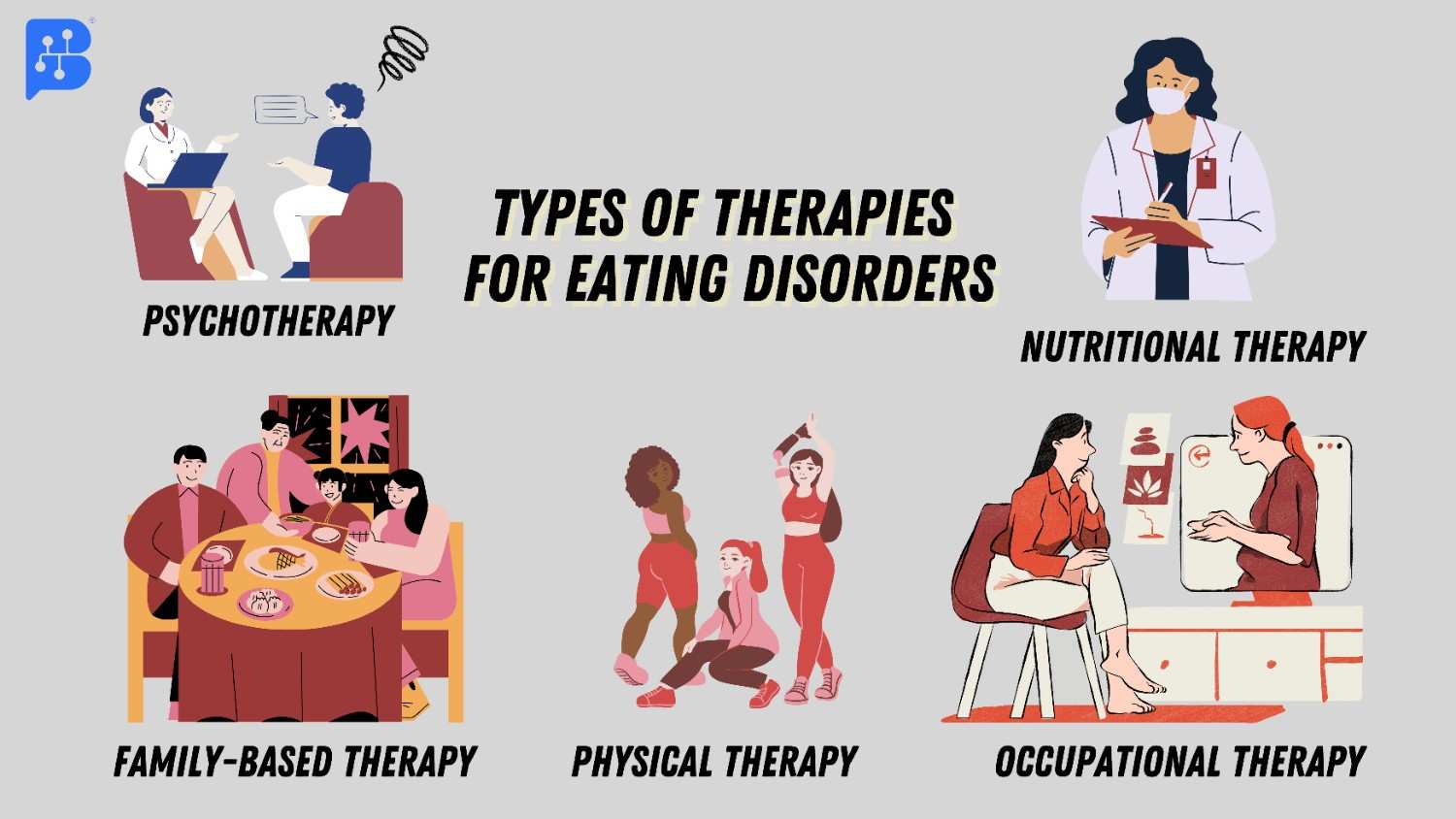

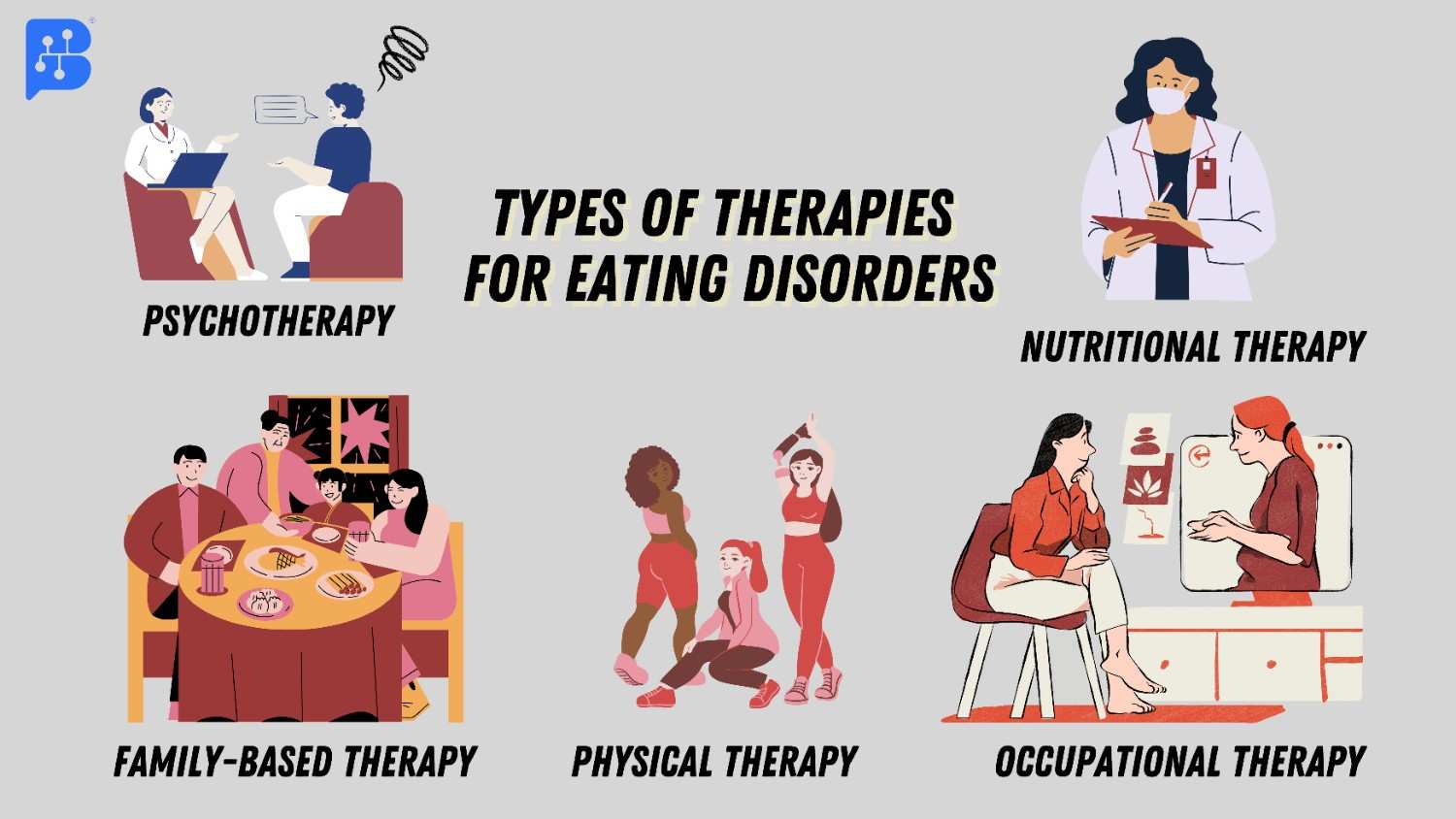

Img-2: Therapies for Eating Disorders.

The picture above shows us many approaches to managing eating problems. It is always preferable to consult specialists to prevent future issues. Among the therapies used to treat include psychotherapy, family-based therapy, nutritional therapy, and occupational therapy. Engaging in physical activity is crucial for maintaining stability and improving health.

Starting with basic treatment, i.e., treating your gut first to improve and stabilize all the affecting factors of mental and physical health, To increase gut diversity, simply by following a few habits like:

-

Consuming a wide range of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. Including probiotics like yogurt, buttermilk, fermented foods like Idli, Dosa, pickles, etc. Also, eat prebiotic-rich foods like onions, garlic, bananas, asparagus, and whole grains.

-

Staying hydrated is very important to maintain good health.

-

Managing stress and balancing mental health through yoga, meditation, and deep breathing exercises.

-

Staying active involves regular exercise and physical activities.

-

Consuming limited processed foods and sugars.

-

Getting plenty of sleep for up to 6-7 hours.

Repopulating the gut microbiome with organisms that reduce Eating disorder-related symptoms, such as Lactobacilli, Bifidobacterium spp., and Enterococcus spp., may result in improved recovery rates. However, increasing the variety of bacteria may affect food choices and habits, resulting in good weight. Restoring the gut microbiota may also address dysfunctional physical alterations (such as a reduced ability to absorb nutrients) that impede recovery and lead to long-term weight gain and better results. Regular exercise may increase α-diversity in the gut microbiota.

Treatment for anorexia nervosa focuses on helping individuals normalize their eating habits and restore a healthy weight. This includes addressing any other medical or mental health conditions. The treatment plan often involves a balanced nutritional approach to ease anxiety around food and ensure regular, spaced-out meals. In adolescents, involving parents in meal support is effective. Body image concerns are also addressed, but they may take longer to improve than eating habits. Severe cases may require admission to an inpatient or residential programme, which can be effective in restoring weight and eating behaviors, though the relapse risk remains high after discharge.

The most evidence-based treatment for bulimia nervosa is outpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy. It assists patients in controlling the thoughts and emotions that feed the condition as well as normalizing their eating habits. The desire to binge and throw up can also be lessened by antidepressants (fluoxetine, for example).

Similar to bulimia nervosa, cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, either on an individual or group basis, is the most successful treatment for binge eating disorder. Research has demonstrated the efficacy of interpersonal therapy and several antidepressant drugs.

Conclusion

To sum up, eating disorders are complex mental illnesses with a variety of underlying causes and manifestations. From emotional eating habits to genetic predispositions, a variety of variables contribute to the development and recurrence of these disorders. New research highlights the connection between physiological and psychological variables in eating disorders by indicating a major role of the gut microbiota in affecting eating behaviors and mental health. Gaining knowledge of the gut-brain axis and how eating disorder pathophysiology is affected creates novel therapy options, such as probiotic supplements and dietary changes. Comprehensive treatment options, however, are necessary to improve general well-being and support long-term recovery from eating disorders by addressing both their psychological and physical components. Meanwhile, ignore your self-defeating thoughts about your weight and looks; instead, follow your heart and adopt a healthy diet. Happy eating!

References

- Feng, B., Harms, J., Chen, E., Gao, P., Xu, P., & He, Y. (2023). Current Discoveries and Future Implications of Eating Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(14), 6325.

- Xu, J., Carroll, I. M., & Huckins, L. M. (2023). Eating disorders: are gut microbiota to blame?. Trends in Molecular Medicine.

- Terry, S. M., Barnett, J. A., & Gibson, D. L. (2022). A critical analysis of eating disorders and the gut microbiome. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 154.

- Thaiss, C. A., Zeevi, D., Levy, M., Zilberman-Schapira, G., Suez, J., Tengeler, A. C., ... & Elinav, E. (2014). Transkingdom control of microbiota diurnal oscillations promotes metabolic homeostasis. Cell, 159(3), 514-529.

- Oliphant, K., & Allen-Vercoe, E. (2019). Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome, 7(1), 1-15.

- Lucka, A., & Wysokinski, A. (2019). Association between adiposity and fasting serum levels of appetite-regulating peptides: Leptin, neuropeptide Y, desacyl ghrelin, peptide YY (1-36), obestatin, cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript, and agouti-related protein in nonobese participants. Journal of Physiology Investigation, 62(5), 217-225.

- https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders

- https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders