- Jan. 16, 2019

- Priyanka

- Microbiome, Nutrition, Diet and Supplements

Vegetables and Gut Microbiome

The Broccoli conundrum – to eat or not to eat?

Starting with, how to make children eat broccoli and then how to eat them correctly - raw or cooked or moderately cooked, then moving on to studying all the health benefits, so much so that claims, such as “broccoli is the only vegetable you need to eat to boost your health”, have been made constantly.

On the other hand “broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables having a dark side”, with specific examples of how it can be bad for your thyroid and other health risks of (at least) having (only) broccoli, have also come up.

Perhaps “to eat broccoli or not to eat broccoli” has been the biggest conflict of the decade!!

To complicate things a bit more, recent peak in interest about our gut microbiota has added another dimension to this conflict.

May be to solve this conflict for once and for all?

Let’s figure it out, shall we?

Diet play an important role in establishing and maintain a healthy gut

We get exposed to microbes right at birth and they start to establish as our microbiome, more often as a unique fingerprint. In our gut, there are trillions of microbes – both beneficial and not so beneficial ones - together having a major impact on our health. There is a huge diversity within the gut microbiome, yet it is cumulatively unique to that individual.

In context of the blog, apart from various other factors, our food, nutrition and diet play a very critical tole in establishment of our gut microbiota.

Generally speaking,

Whole grains, beans, fruits and vegetables packed with nutrients, seed our gut with healthy bacteria and helps in maintaining gut diversity. Eating a lot of green leafy vegetables and low-sugar fruits establish our gut with healthy and diverse microbes. Fibre-rich foods are essential for gut health. Beneficial microbes absorb vitamins to enhance immunity and decrease inflammation.

To understand this better, here are some specific classes of vegetables and how they help to establish and sustain a healthy microbiota of the gut.

Resistant starch vegetables for gut microbiome

High starch content of some foods has been known to have adverse effects, and consuming excessive starch can indeed lead to health problems.

However, all starch is not bad and its misconception that high starch is detrimental to health.

A sub-group of starches, called resistant starch, has lately gained importance for its beneficial impact. Specifically, individuals with digestive problems, by slowly adding such foods in one’s diet, have responded with alleviated symptoms like reduced gas and discomfort, along with an overall improvement in their digestive capabilities. Largely, such foods are deemed helpful in IBS, colitis, some allergies cases and in autoimmune diseases.

The primary reason why resistant starches are important is because of their ability of enhance friendly bacteria in our colon. Resistant starches cannot be broken down by our gut (they ‘resist” digestion). Unlike other starches, instead of getting digested and being absorbed as glucose, it passes through the small intestine to the colon, where it gets converted into favourable, energy boosting, inflammation supressing “short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)” by the intestinal bacteria. In turn, the process gives the beneficial bacteria an abundance of nutrients for their growth and sustenance.

Foods rich in fibres and gut microbiome

Similar two-way streak has been observed between fibre rich foods and gut microbiome. Fibre rich foods boost the growth of beneficial gut bacteria (mostly, Bifidobacteria). Largely, there are two types of fibres, viz., soluble and insoluble fibres. Soluble fibres help in lowering blood glucose levels and LDL cholesterol, whereas, insoluble fibres concentrate more on cleansing our digestive system. Radishes, leeks, Jerusalem artichokes, asparagus, jicama, carrots and many others belong to the class of fibre rich foods.

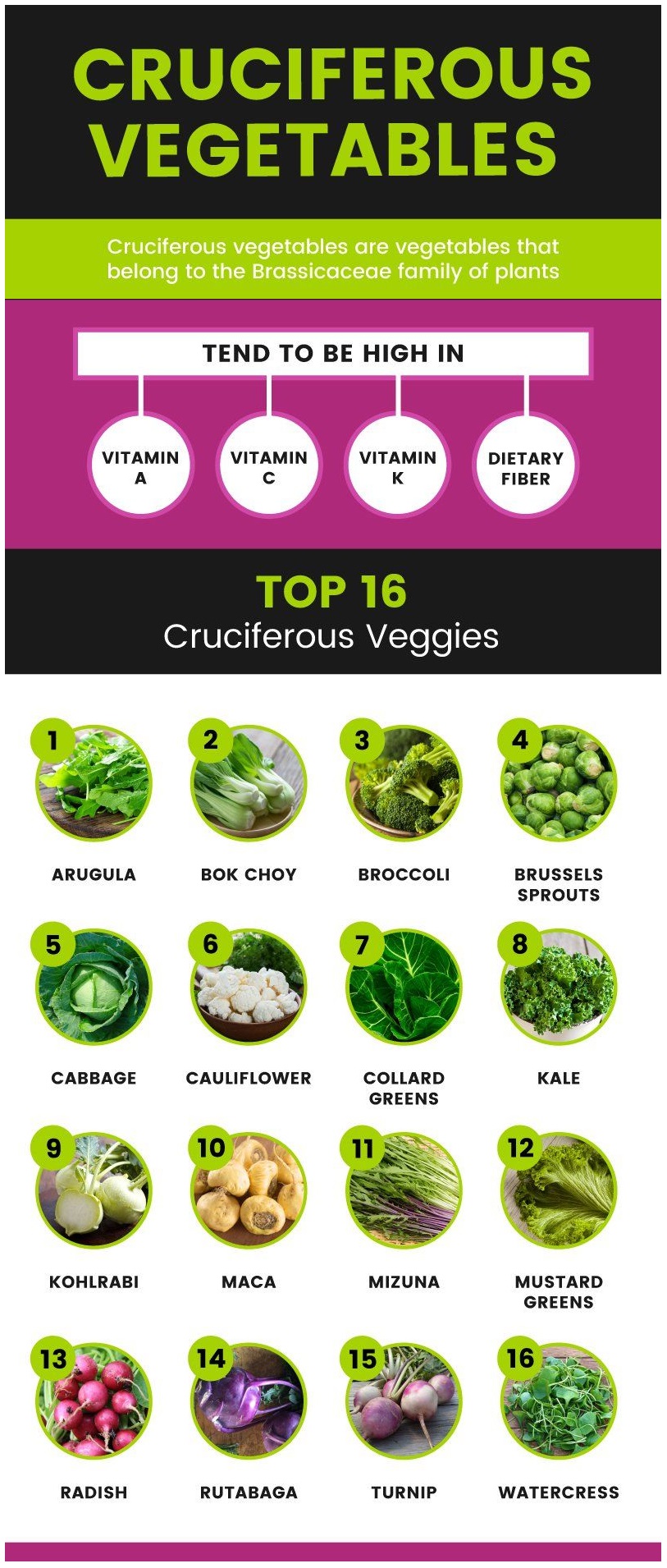

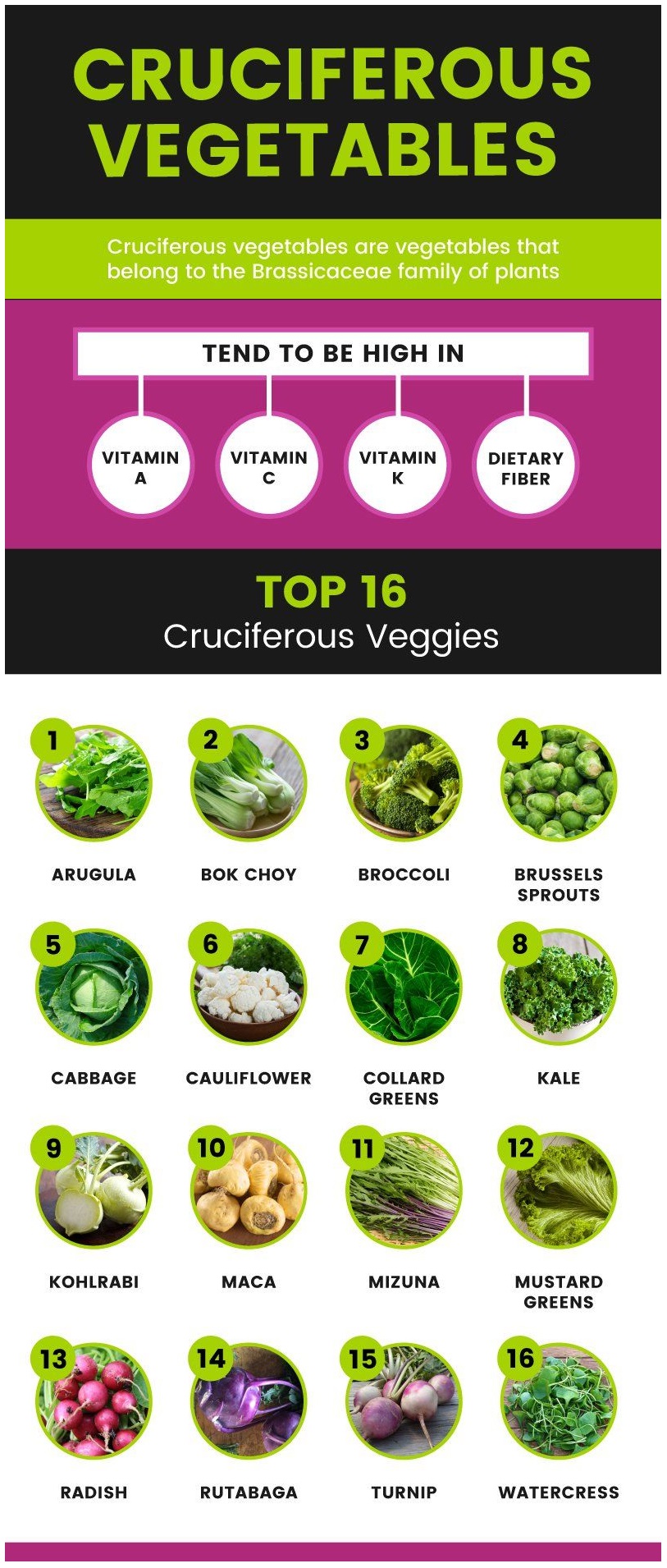

Cruciferous vegetables for gut health

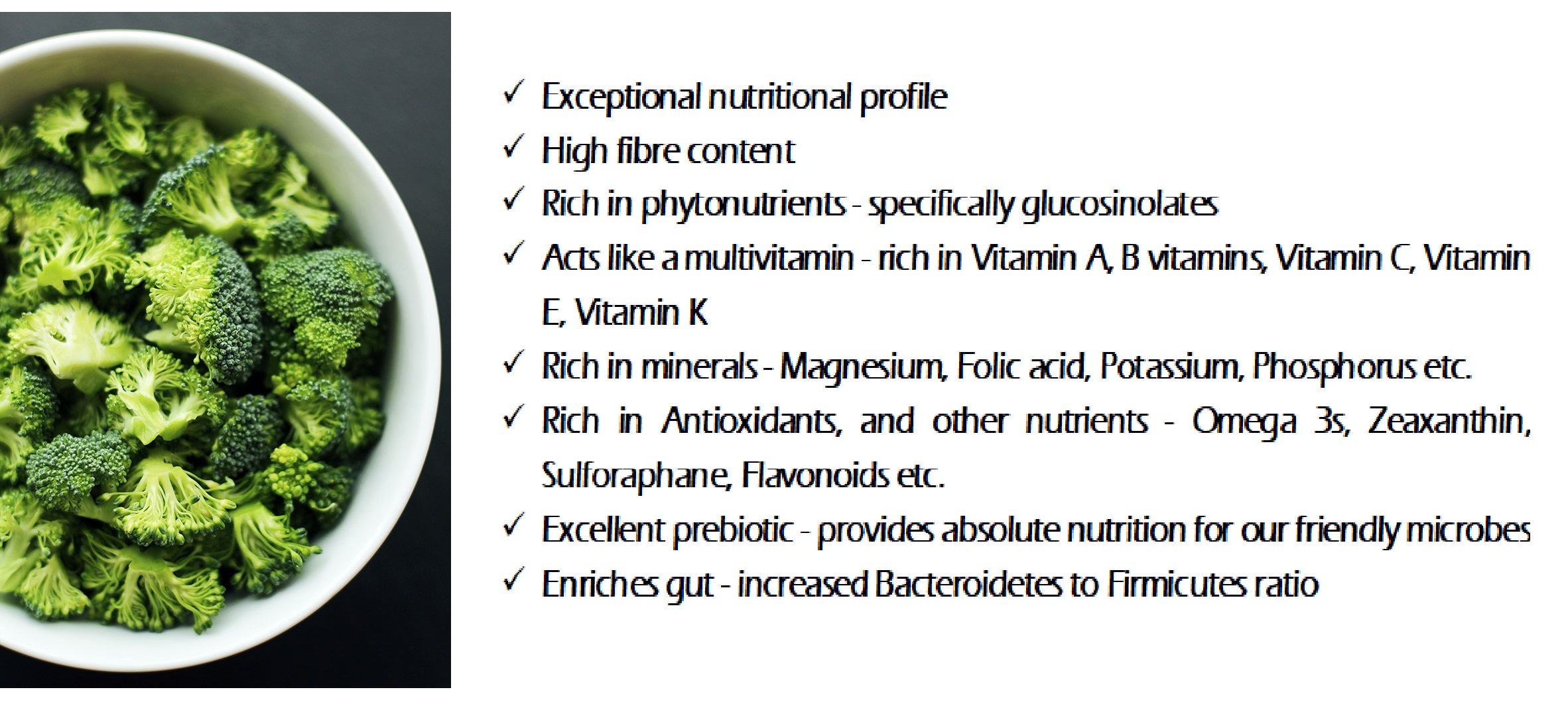

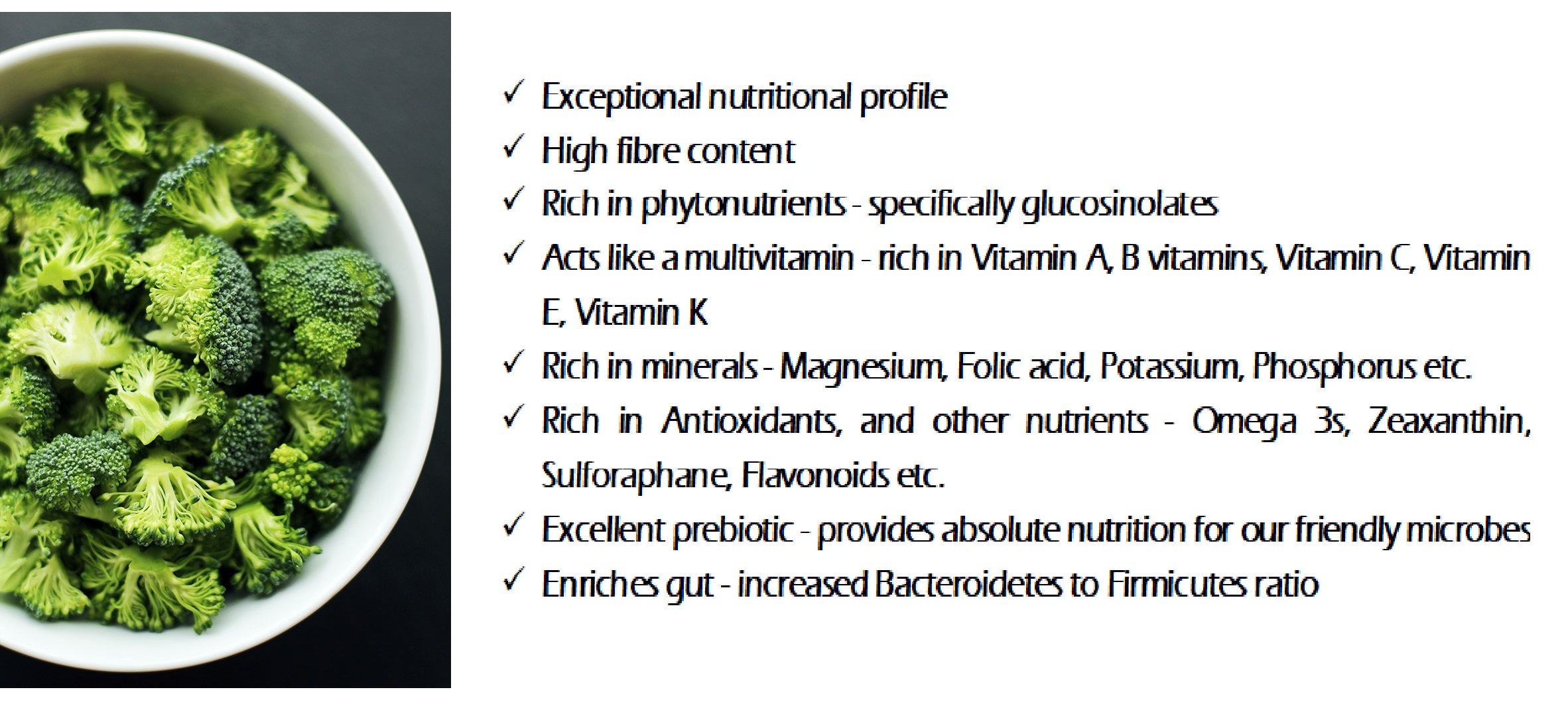

This category of vegetables has been estimated to possess high fibre content, and hence has similar mode actions and beneficial effects as fibre rich foods, described above.

The most interesting aspect of cruciferous vegetables, that has set itself apart from rest of the veggie categories, is the presence of distinctive phytochemicals, such as glucosinolates.

Further, Isothiocyanates (ITCs) are a group of bioactive compounds that are generated by the break-down of glucosinolates and are deemed to have many health benefits, including anticarcinogenic properties. Various researchers have reported that, ITCs are potential chemoprotectors, they fight cancer and supress the neoplastic effects of various carcinogens at different organ sites. A detailed analysis of ITCs and glucosinolates, post consumption of dietary crucifers, have also yielded similar observations, adding support to the published reports.

The most fascinating aspect here is the connection between these phytochemicals and our gut microbiome.

For dietary crucifers to be effective as anticarcinogenic, glucosinolates must get converted to ITCs. In plants, myrosinase enzyme is the enzyme responsible for this conversion. However, these myrosinases gets deactivated after cooking. And, here enters the gut microbiota!!

Certain groups of bacteria populating the human gut have myrosinase-like activity, which metabolizes glucosinolates to ITCs and hence re-instating the anticarcinogenic property of cruciferous veggies. Hence, when we consume cooked cruciferous vegetables, we depend on gut microbiota to convert glucosinolates to ITCs.

Diversity in vegetables, not quantity or specific type, is key to good gut health

The same studies that established this fascinating connection, also identified diverse bacterial species that can degrade glucosinolates. Similar observations have been made with digestion of fibre rich foods, resistant starches and many others. These strongly indicates, that any health benefits that is conferred by these vegetables are not only dependent on the quantity and type of vegetables we consume but also depends on bacterial composition of our gut.

Further, it is a two-way streak, where eating more vegetables alters the bacterial composition of the gut, which in turn aids the digestion of these foods. A diet including many different types of vegetables (consisting of 30 or more different plant types each week) has been correlated with a much higher diversity in their gut microbiota. This pattern was noted irrespective of the type of diet consumed by the participant, greater bacterial diversity was recorded in both meat-eaters and vegans, so long as they consumed a large variety of vegetables and plant matter.

So, should we eat broccoli or not?

Let’s make a simple check list and see if broccoli fits the bill.

So, yes!!

You can eat broccoli

But remember

“Diversity in vegetables, not quantity or specific type, is key to good gut health”